Mikado Method: Example

Moving Furniture

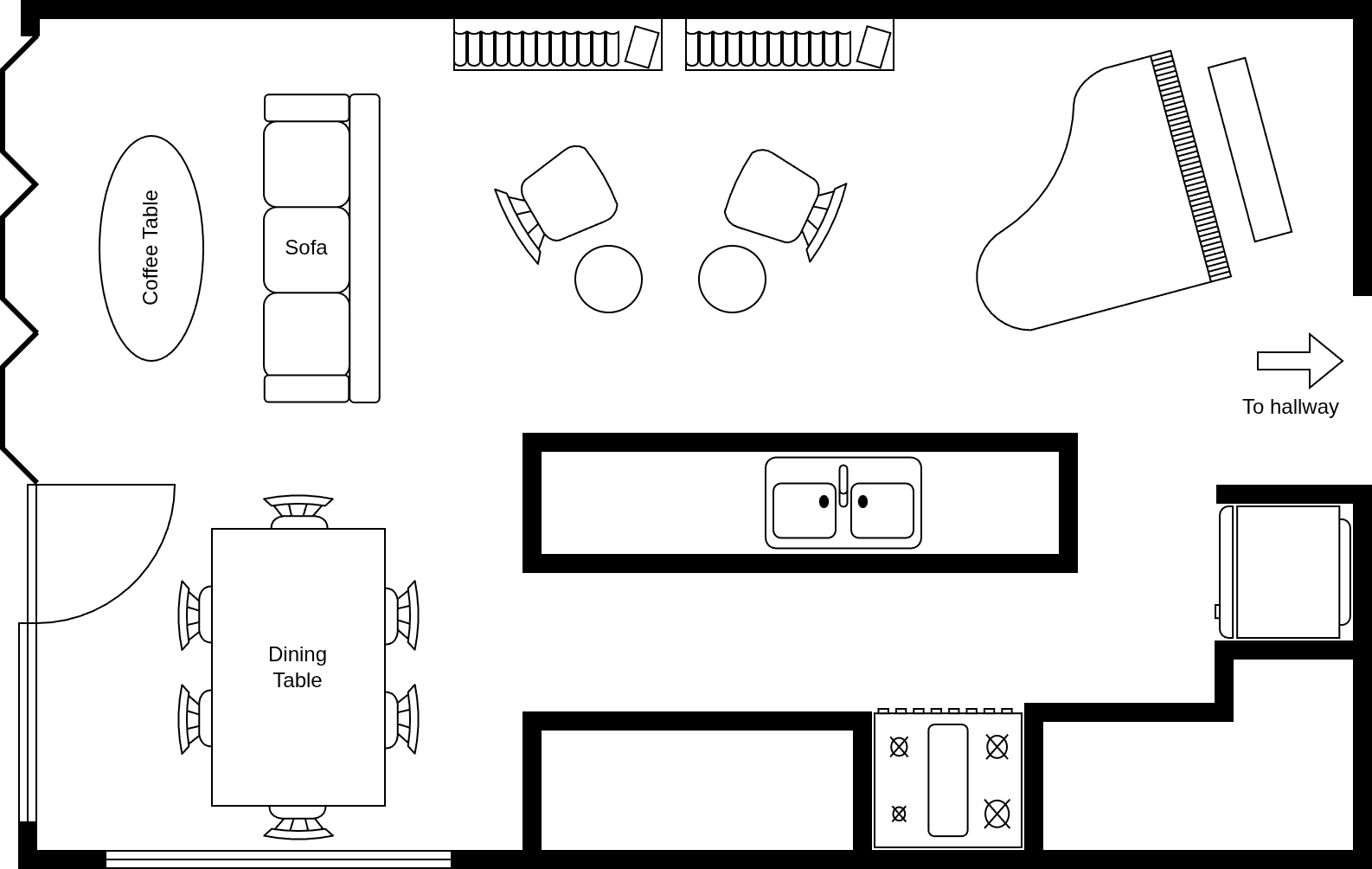

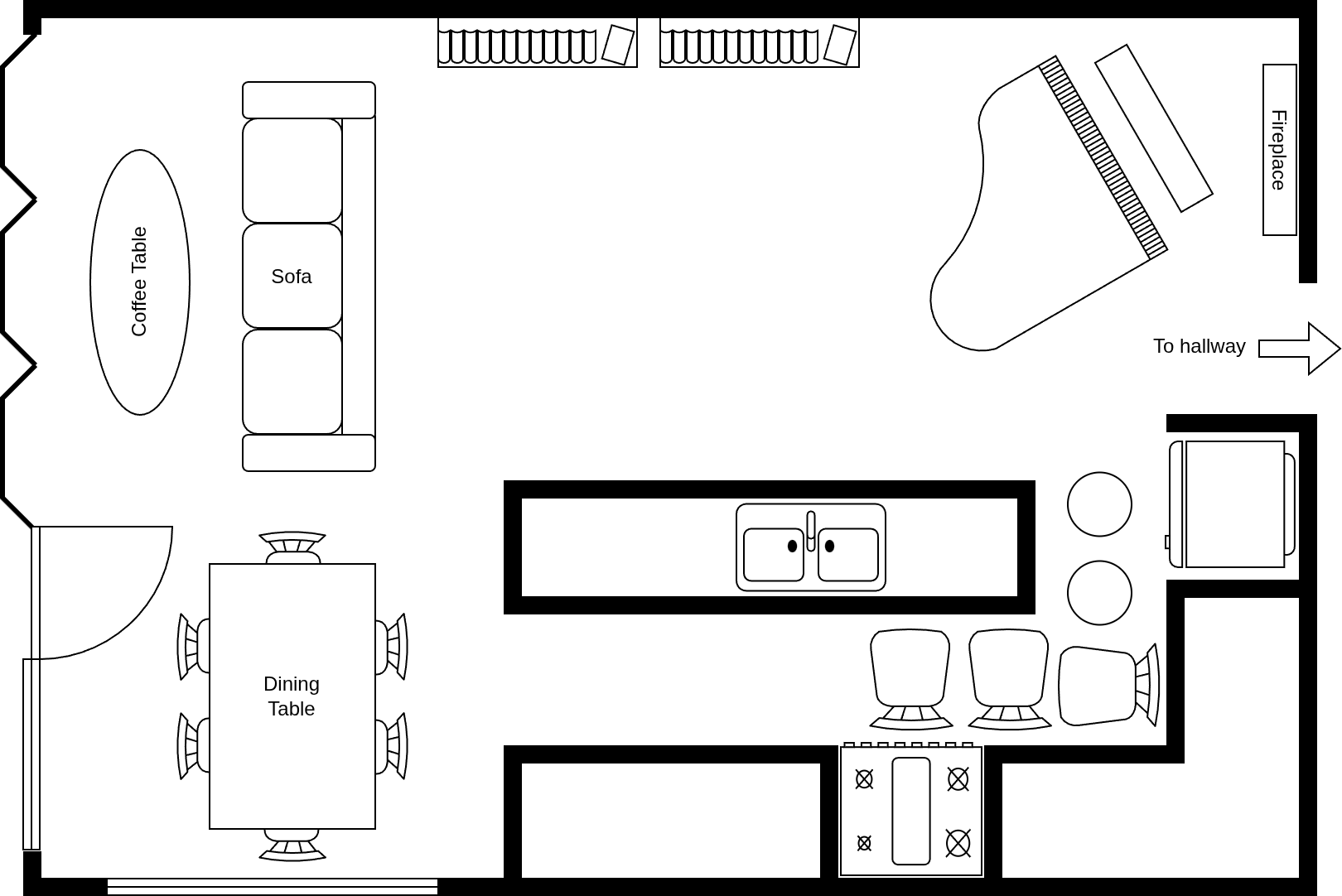

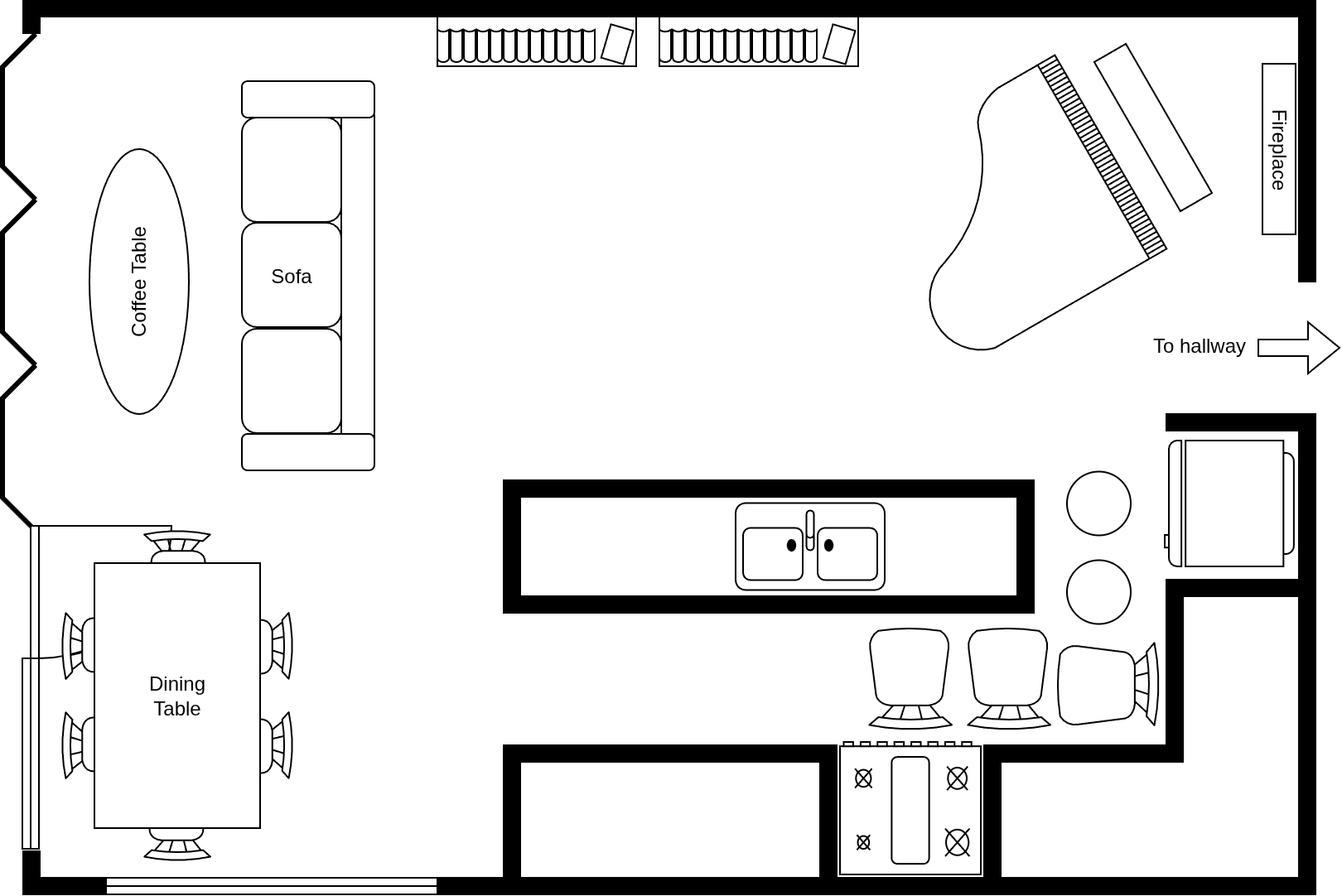

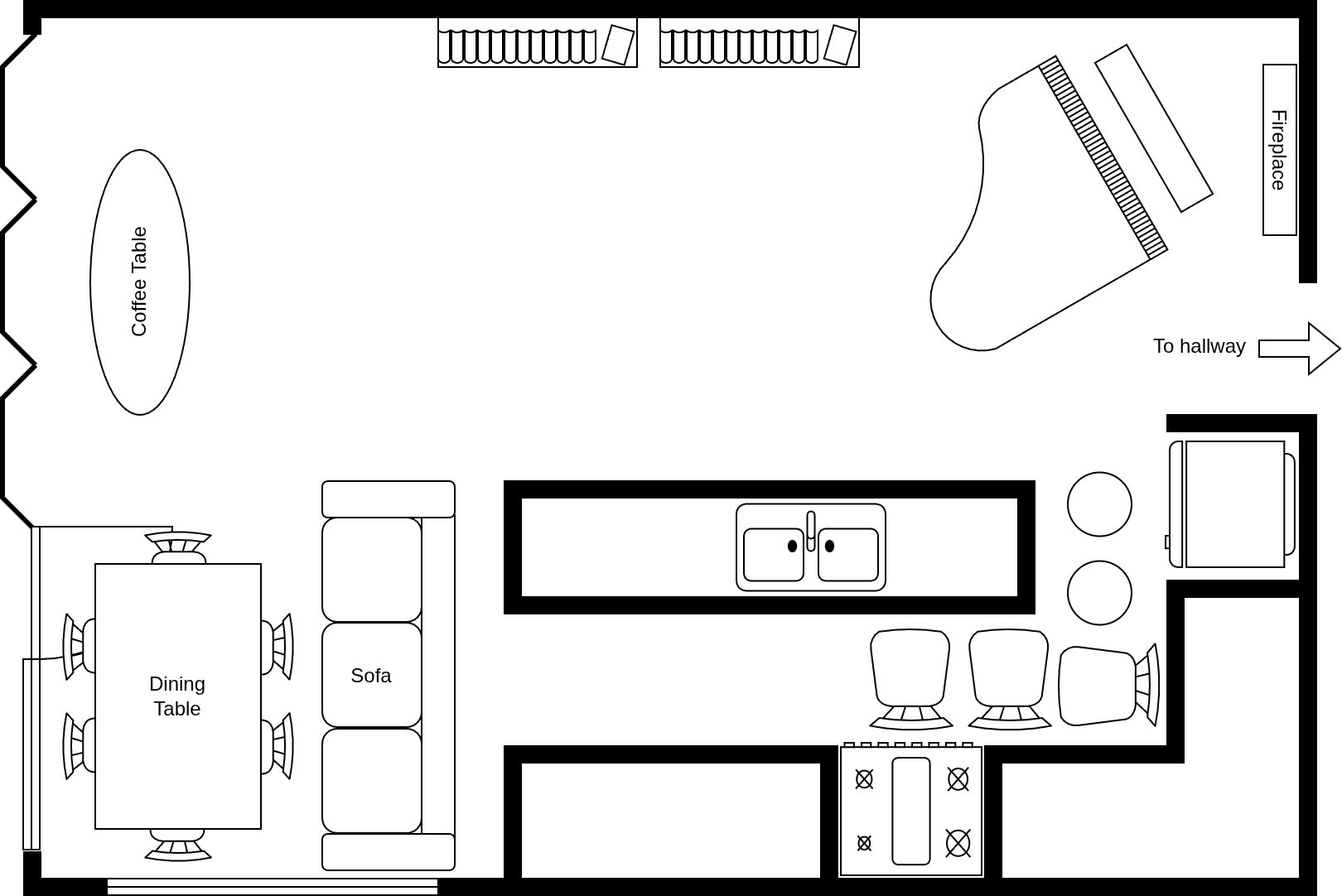

Let’s start with our hypothetical living room. It’s nice, but our resident pianist could use some better lighting. We would like to move the piano to the other side of the living room to make use of the light from the windows.

The Goal

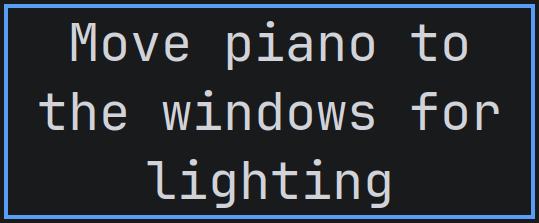

We always start with the goal - it may be completed, but never removed. It should be both concise and representative to the effect that a colleague could pick up the work and know what to do. It is also wise to mention the value it brings to the stakeholders.

Experiment

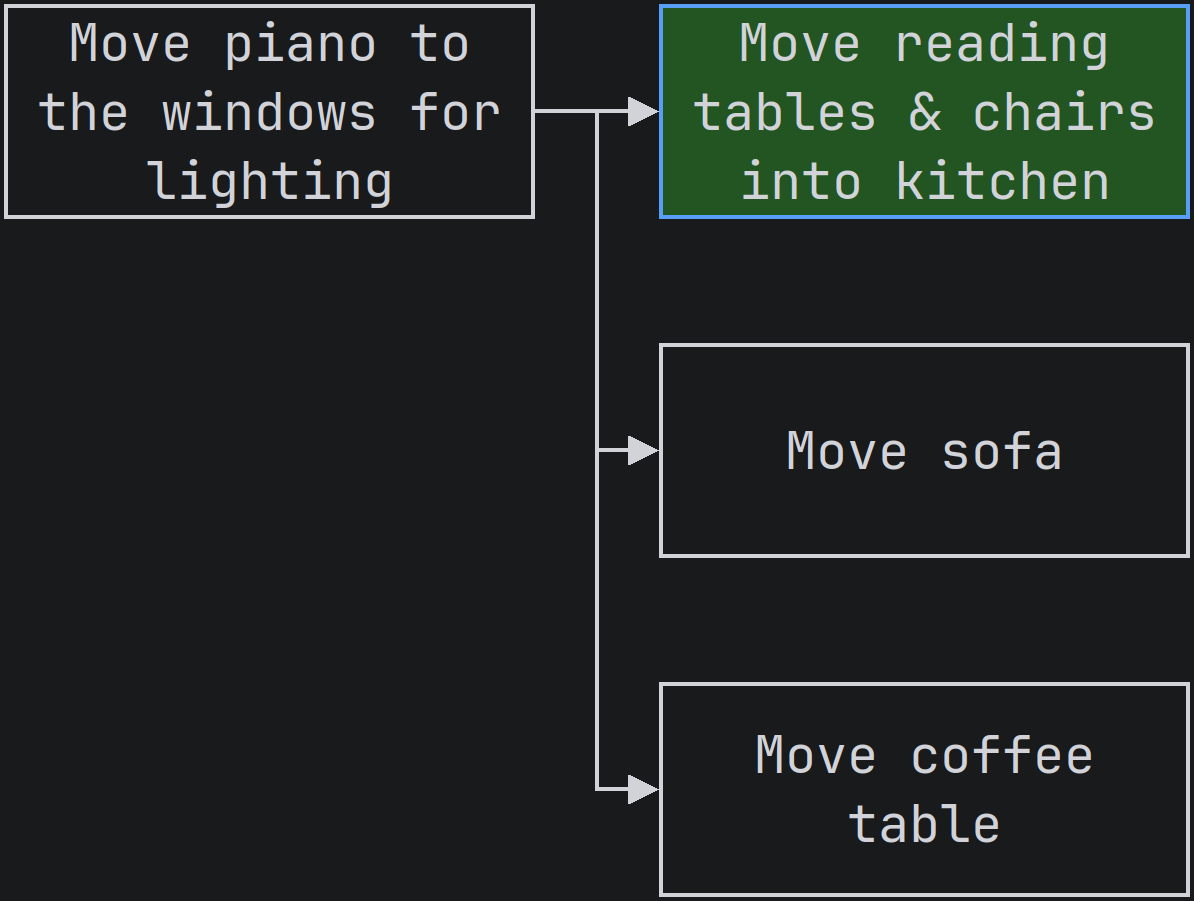

We start with a naive experiment for the current leaf node, which happens to be the goal: naively, let’s just move the piano. Alas, the reading chairs & tables, the sofa, and the coffee table are all in the way! Although the experiment “failed”, we have some good news! We discovered prerequisites (dependencies) which need to be resolved before we can move the piano.

Visualize

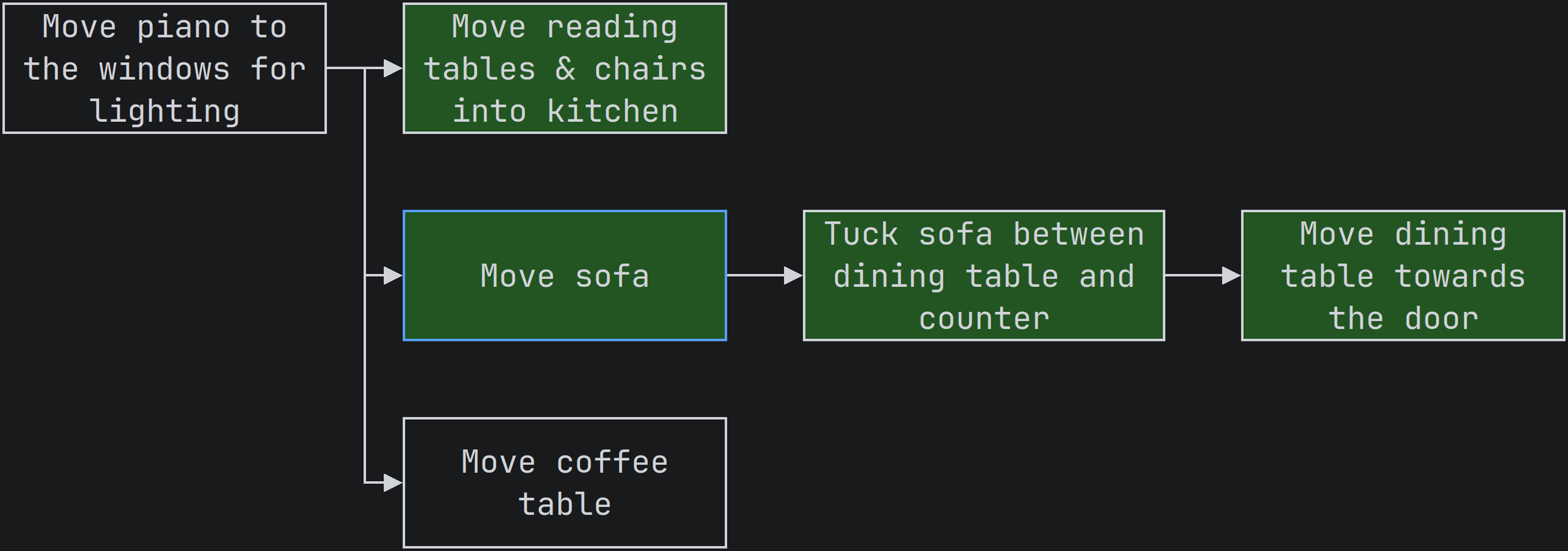

We take a moment to come up with immediate solutions to the issues at hand. By looking at the floor plan, we realize that the kitchen is large enough to hold the reading chairs & tables, which is easy enough. The sofa and coffee table are a bit more complicated and need some additional effort, which we’ll get to in a bit. With knowledge in hand, we can visualize these prerequisites on the graph. We now have three items which must be resolved before we can make another attempt at the goal.

Undo

Before we do anything, we undo the move of the piano. Thankfully, it’s on wheels and it’s easy to move.

An Experiment That Works

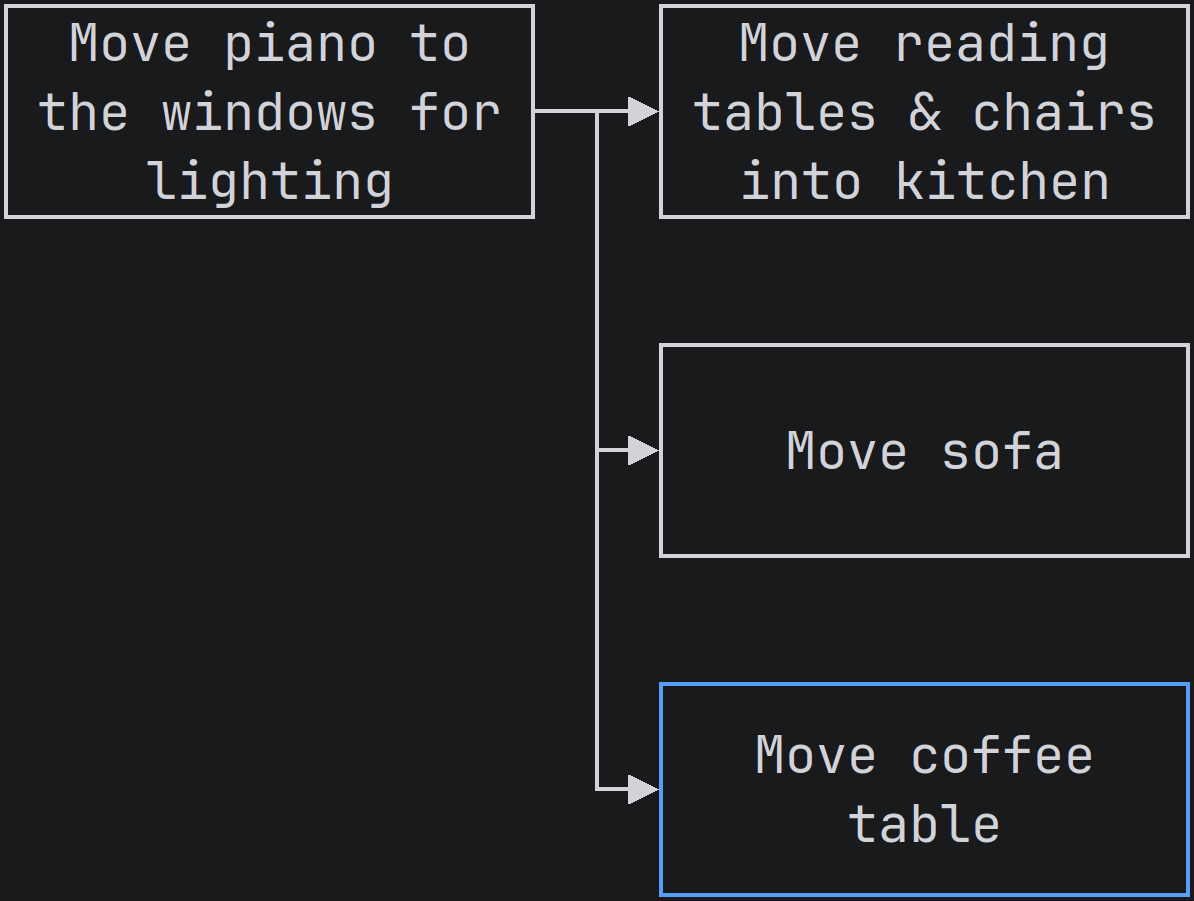

We have three leaf nodes and one obvious one which can work: moving the reading chair and their tables into the kitchen. Let’s do that!

Since this just worked, we just bounced into the execution phase!

Analyze

The tables and chairs are tucked away for the time being, which will allow us to move forward, but not before we record our progress!

Check

We can check off that node and continue on with our work. If this were pen and paper, we would put a check-mark on the node. However, Easely notes this change with a green background.

Since this analogy of moving furniture isn’t a software project, our commit will be to leave the furniture where it is at the moment.

The Sofa?

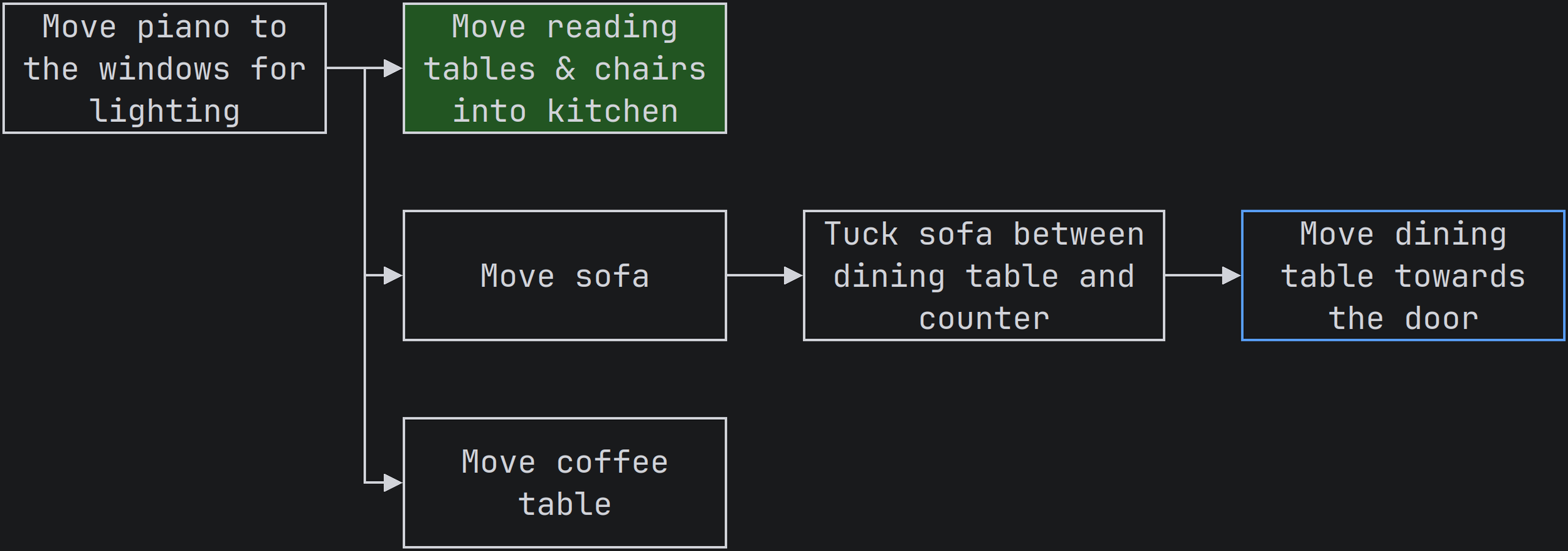

We select one of the prerequisites on the graph and attempt an experiment from there. We try to move the sofa, but it’s clear that we need more space than sliding it next to the island; this option does not make it into the visualization since it’s not a viable solution. We have to make some more space. At this point, we’re exploring again.

We do a quick measurement and find that we have enough room to slide the sofa next to the kitchen table, if me move the table towards the door.

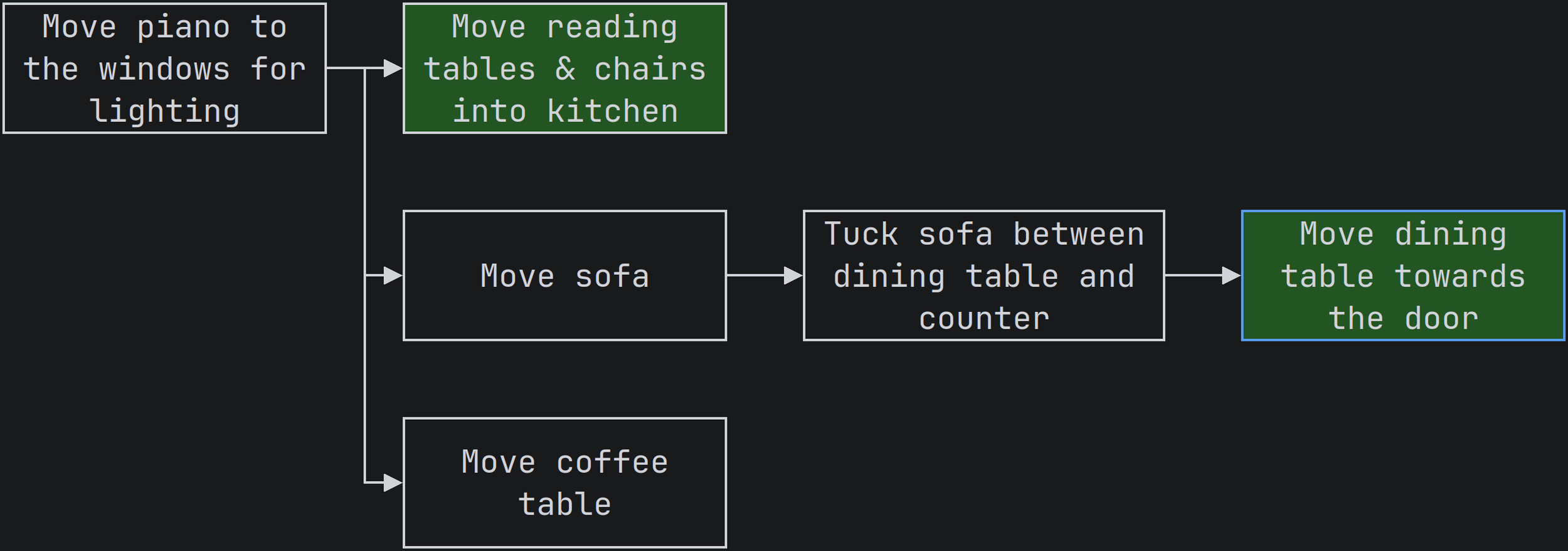

The Table

Now that we are getting the hang of this, we can move the table, analyze the situation to make sure we have space, and check off that node!

The Sofa!

We have some space to tuck the sofa, let’s do that. Furthermore, we have two nodes which we can check off: “Move sofa” and its child.

Wisdom for the Mikado Method

Commitment to naive simplicity in implementation.

Common Troubles

To Undo or Not to Undo

We are human beings and we are vulnerable to the sunk cost fallacy: the more we invest, the harder it is to pull the plug. This hits home for software development as well. The larger the diff of our working tree, the harder it is to undo - it just feels wrong! This is a trap.

The longer we go without undoing our work, the larger our diff becomes, the more context we must juggle in our brains, thus the pace of work continues to slow down.