Mikado Method: Primer

The Mikado Method was developed by Daniel Brolund and Ola Elnestam during a large refactoring effort with significant difficulties. They did a bunch of work as a revolutionary change while the rest of the team charged forward with continued product development. This, of course, created a cycle of ever-slowing and disconnected work from the rest of the team. Their moment of clarity came when they reverted their code: they were just doing the work in the wrong order.

We can think of the Mikado Method as a means of moving furniture: if we want to move the piano to the windows, then we’ll need to move the sofa out of the way, which means I need to make room by temporarily moving the dining table. This simple example describes the exploration of the work in a forward direction and the execution in a backward direction: the dining table is the first move to make. For this system to work, we need a graph to record what we need to do as a tree of dependencies.

The Graph

The Mikado Method makes use of a graph to organize our work. This graph also becomes a produced artifact of our process, showing what we did, how we got there, and the scope of the changes.

Symbols

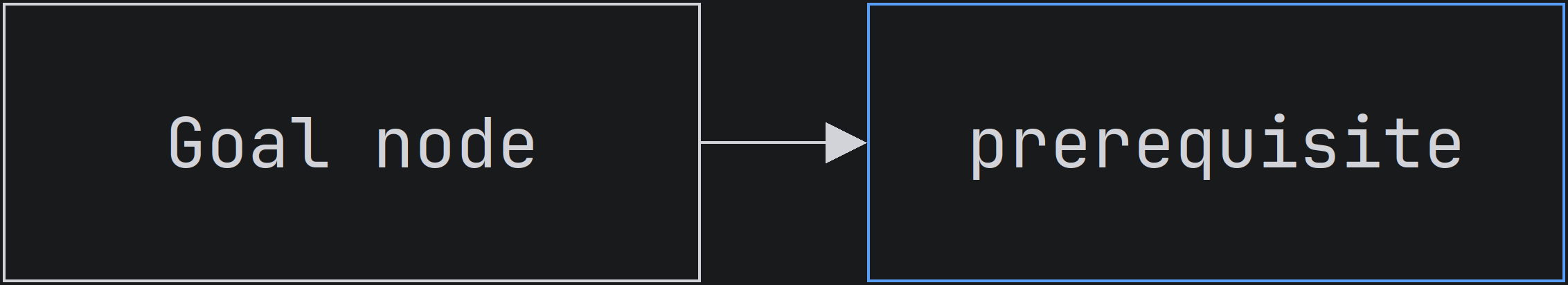

The graph uses two main symbols: nodes and arrows (in the book, Ola and Daniel use a double circle for the root goal and a single circle for the other nodes, though those are semantic differences; we’ll stick to two symbols for our use).

The graph a directed acyclic graph, meaning that it has no circular pathways. Counter-intuitively, there is a possibility of encountering a false cycle, where it appears like there’s a loop, but all we need to do is break down a node into smaller pieces and the loop is resolved.

Exploration

We first start with the goal as the single node on the graph, though we can explore from any node which is not yet complete. We explore by following these steps:

Experiment: implement a prerequisite (node on the graph) using a naive change, which might break something;

Visualize: jot down the solutions to all discovered issues as new dependent nodes;

Undo: reset your working tree to a completely clean state; and

Repeat: select another leaf node and experiment from there

The undo step is the most difficult to get used to; the sunk cost fallacy is a bias to be aware of. We have a tendency to continue working on our current path and invest more into it, even when we observe we are slowing down with an ever-growing working tree of changes. The system of the Mikado Method works best in smallish steps. There’s a balance to granularity: too fine and the process can become a burden of overhead with deceptively large graphs, too coarse and we pay a high opportunity cost as we get lost in our current changes. It takes some practice to get used to.

Sometimes an experiment will just work - no issues! In that case, we bounce to the next phase: execution.

Execution

The execution phase begins when an experiment reveals no issues. This is when we start winding back on our work and following the chain of prerequisites until we either need to explore again or we complete the goal. We execute by following these steps:

Analyze: make sure the changes in the working tree make sense to commit;

Check: check off the associated node(s); and

Commit: commit those changes

Sometimes, we analyze the code and find out that it doesn’t really make sense. Making sense means that it compiles, tests pass, the product may be shipped in that state, and colleagues won’t be surprised if they look at the code. Perhaps it compiles, the tests pass, but all we did was add an unused method. In this case, try another experiment with a related node. Once it makes sense, commit that code! If at any point you must explore again, undo all changes to the working tree and bounce back to the first phase: exploration.

Sometimes, the check step will result in only the goal remaining unchecked. If there is more work to be done, it’s back to the exploration phase! Otherwise, you completed your goal! Enjoy your achievement!

An Example

Let’s see how we can use the Mikado Method to describe moving furniture. It’s a clever analogy for the world of software to which everyone can relate.

Wisdom for the Mikado Method

Commitment to naive simplicity in implementation.

Common Troubles

To Undo or Not to Undo

We are human beings and we are vulnerable to the sunk cost fallacy: the more we invest, the harder it is to pull the plug. This hits home for software development as well. The larger the diff of our working tree, the harder it is to undo - it just feels wrong! This is a trap.

The longer we go without undoing our work, the larger our diff becomes, the more context we must juggle in our brains, thus the pace of work continues to slow down.